In many ways, the true progress of the developing nation can be judged from the purity and the advancement of the entrepreneurial spirit – both imitative as well as innovative – that the country has nurtured over the course of its development. This spirit is a cumulative product of an array of factors that also determine the nature and scope of industry in the country, from things as basic as the availability of raw material to things as complex as prevailing social norms or governmental policy. With the lush landscape of opportunity that characterizes the Indian market today and the number of startups that are springing up across India to solve problems, provide services and products, and take bold steps to reap profits, it is interesting to ask that elusive question: How has, then, the entrepreneurial spirit of India grown from the ancient ages to the present, when there is quite evidently a flourishing culture of innovation and enterprise?

This is exactly the question that we shall seek to answer through a trilogy of articles. These articles shall trace the evolution of the entrepreneurial landscape in India from the early ages to the state in which it exists today. The first article in the series shall concern itself with entrepreneurship in pre-18th century India. The second article will explore entrepreneurship in India between the 18th century and her independence in 1947. The third article shall act as a concluding segment that briefly touches upon entrepreneurship in the country from 1947 to the present. It is important to note that this trilogy acts as an introduction to a series of articles that talks about the development of entrepreneurship in the country, a few success stories of entrepreneurs that started out their businesses as small-scale enterprises and became highly successful and concludes with a brief analysis of the policies and institutions introduced to promote entrepreneurship among the underprivileged.

Entrepreneurship holds the potential of being the great equalizer, both in the economic and social sense; capable of not only alleviating poverty but of having ripple effects and reverberations throughout society in the form of greater employment, greater financial health, and greater empowerment of all the communities involved in the entrepreneurial effort. It is hoped that through these series of articles, the writer can bring about a change, however small, in the readers’ perceptions about entrepreneurship and establish the effort as a noble one, in that it benefits not only the individual, but society as a whole.

The Ancient Times: Entrepreneurship in Pre-18th Century India

Let us begin by understanding what exactly entrepreneurship is before we delve into its history. In its basest, most classical form, entrepreneurship can be understood as the ability to identify new economic opportunities and exploit them. The entrepreneur possesses a kind of “disruptive innovative energy” that breaks the “cake of custom”, in the words of Edwin F Gay. So it is that we encounter the first setback to the birth of India’s entrepreneurial class. In ancient times, the cake of custom in India’s case was considerably rigid, manifested in the form of the Varna (caste) system. According to the tenets laid down by this system, trade of any form and commerce were solely to be the profession of a single caste, the Vaishyas (merchants). These restrictions stifled any hopes of entrepreneurial activity from the three other Varnas. The Vaishyas tended not to deviate from their traditional roles as bankers and money lenders.

Unfavourable ‘Climate of Enterprise’

While the thoughts of business historians following Weberian views (after Max Weber) seem to believe that it was the fierce following of and devotion towards the Hindu scriptures and customs that hampered the rise of entrepreneurship, Dwijendra Tripathi, a renowned scholar of business history, believes it may not just be this to blame. While such religious and cultural factors may have played a role, he maintains that W.T Easterbrook’s concept of “climate of enterprise” – which stressed giving importance to the “material environment” rather than the cultural or religious environment – had a more pivotal role to play in the conduct of the mercantile and the non-mercantile classes of old and could better explain their apprehension to deviate from their traditionally defined roles.

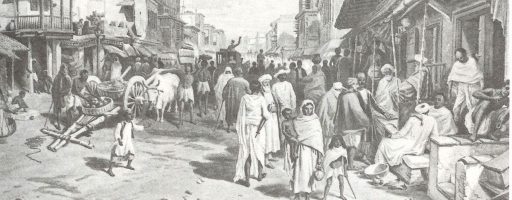

The material environment in India during those days was hardly conducive for stoking entrepreneurial spirits. India before the 18th century was a politically and economically volatile subcontinent. Even when political unity existed, the lack of an effective communication system was a severe impediment to industry. Political fragmentation had led to the creation of multiple currency systems that had made it hard for goods to be traded over long distances without difficulties. Inefficient and exorbitant custom duties also negatively affected the sale and purchase of goods, hurting the producers and discouraging individual enterprise. The scant data about taxation during the Mughal rule that Tripathi analyzed suggests that taxes were high and an impediment to entrepreneurship.

Discouraging Economic System

Thus, until India was open to international trade for day-to-day requirements in the 18th and 19th centuries, its economy was characterized by self-sufficient village aggregation units interspersed with major towns and cities. These village units were self-sufficient in many respects. Village functionaries like the carpenter, weaver, or the blacksmith were paid for using the year’s harvests. As C. N Vakil notes in the Technological Change in India, “The economic prosperity of the whole community was immediately linked with the agriculturists’ fortune.”

This era also witnessed the formation of guilds. Guilds were primarily involved in the organization of production. They also acted as places where individuals under it could receive security and maintain their social status. The guild members typically specialized in a particular craft such as pottery, carpentry, and so on. They emerged as places where one could hone their skills and impart their knowledge to the younger members. Guilds framed rules of work, maintained the quality of finished products and fixed prices to safeguard both the interest of the customer and the artisan.”

This economic system was a highly discouraging environment for the development of entrepreneurship, as Phiroze B Medhora notes:

“Thus arose a system in which birth decided one’s function and place in the social system, and economic reward depended upon function and did not vary (except for trading communities in towns) with the effort put in. Religion, particularly the caste system, tended further to inhibit change and lend rigidity to the economic system. Combined with the village organization (and payment) system, it made for a framework of society in which the modern industrial system could not have arisen as a natural development from within.”

Therefore, we must conclude that both the cultural and the material environment before the 18th century was not conducive to entrepreneurial growth. It is no surprise that individual enterprise was minimal at the time, with business being the prerogative of just one class of individuals. This hostile environment persisted, Tripathi holds, until the advent of the European powers.

(Note from the Author: I believe it is pertinent to set before the reader a caveat: I am not an authority on this subject. The document before you is a culmination of weeks of secondary research, and credit, if any, must flow to the authors that I have referred to in the course of my study. As such, I feel compelled to highlight two prominent scholars that stand out: Mr. Dwijendra Tripathi and Mr Phiroze B Medhora. Modern Indian Business Studies owe a considerable amount to the efforts of both of these scholars, and their works are a must-read for all who wish to educate themselves on the subject. I sincerely hope you enjoyed reading this article.)

Anjaney Sudhakaran is an undergraduate business student at the Indian Institute of Management, Indore. His academic interests include economics, history and statistics. He loves to read fiction and is an ardent movie enthusiast